'The Light' is pretty much the only Common tune I've ever cared for and such was my antipathy for the rapper that for a long while I considered the track a kind of sample-delivery machine: you wait patiently through the verses for the gorgeous, glistening [sampled] chorus...

Simon Reynolds over

here in a blog about J-Dilla.

Fingers twitching spasmodically while reading... Dilla important to backpackers but never a backpacker... RZA was 'unquantized' well before Dilla... other... pedantic... unnecessary... observations... [

swallow – gasp]

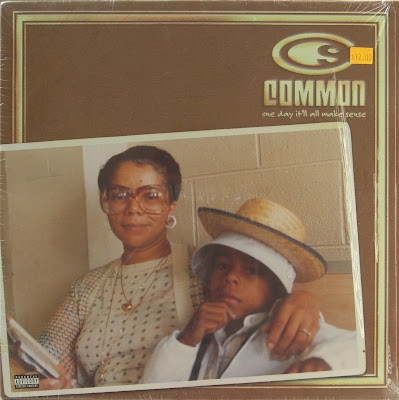

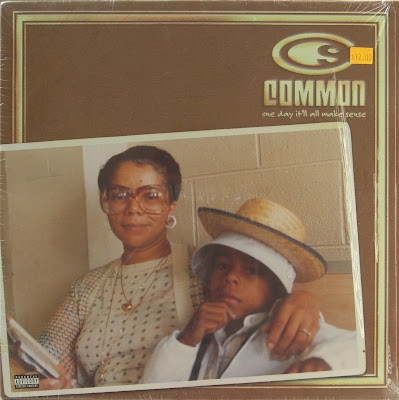

But as the first in a series of shameless fanboy 'I Love _____' posts, I want to make a case for Common, justify his existence a little bit, after Simon’s critical-beatdown-in-passing. Specifically, I want to make the case for his ’97 album

One Day It'll All Make Sense.

This record came out in the autumn of that year – a year that hardly compares release-wise to the riches of '92-'94, but is properly significant in hiphop history. Consider the following three records.

Late spring, Puff Daddy's ‘I'll Be Missing You’. The inauguration of hiphop as commercially supreme musical force. Took a hiphop subgenre which was already tragically prevalent – the elegy to a fallen friend – and Hallmarked it, made even the funerary oration an excuse for the prominent display of superbikes, and a messianic all-white dress code. Sold itself to a massive crossover audience using a sample of The Police: a black impresario (Coombs) re-digesting a band which was already a re-digestion by three white guys of black Jamaican culture. The logical product of this kind of no-added-value cannibalism was the career of Jennifer Lopez (Sean Coombs’ later girlfriend), in which classic hiphop beats (Craig Mack's ‘Flava in Ya Ear’, The Beatnuts' ‘Watch Out Now’), already works of sampling, were sampled again, double-filtered for maximum pop slick. I could go on.

Late summer: The anti Puff Daddy, Company Flow's

Funcrusher Plus. An album full of dazzlingly horrible ideas; beats like bruises, rhymes bipolarized into hyperactive thought and catatonic depression. Difficult, malevolent, serrated, a record as fiercely anti corporate culture as anything by Ian Mackaye or Steve Albini. But one that, as good as it was, had a pernicious effect: it validated an entire subsequent anti-mainstream subculture, indie hiphop, art hiphop, that succumbed to the logic of the purist’s ghetto, in which miniscule sales became a proof of quality / credibility. An example of the classic as uncopyable, a cul-de-sac.

Late summer:

Wu Forever, the record which, if you believed the RZA’s hype, would be the Rosetta Stone for music’s next millennia, the blueprint for its past, present and future – don’t you see the letters RZA in Mozart? he would ask interviewers at the time – a bringing together of the arcing solo-career vectors of Meth, ODB, the GZA, RZA, Ghost, Rae et al into something that would transcend even the sum of those colossal parts. Turns out, like a bad marriage ‘forever’ meant '93-'97... Well, I do think there's a good single album struggling to get out of

Forever's labyrinthine immensity. And

Supreme Clientele and

N**** Please were still to come. But still, as Owen

observes, from this point on the Wu were in decline.

So, the end of a good era, the start of a bad, and a subnarrative that looked like a new beginning but was really more of a culmination.

This is the scene into which

One Day It’ll All Makes Sense issues, so it’s not surprising if it got lost a little in the fuss. But it’s a record that reflects those growing pain convulsions, all the eddying tensions of cash, cool, credibility, cartoon violence or complexity; it amounts to an argument over what hiphop is, should or can be. There are tracks that just thump with that offhand steadiness of peak-era Evil Dee, Premier or ATCQ: ‘Invocation’, ‘Real Nigga Quotes’, ‘Hungry’, ‘Stolen Moments Pt II’. But there are also moments where Common tries to push things forward, ask messy existential questions in a way that could lead him into (potentially) tediously ‘mature’ pastures. This is an album that addresses something Matt Ingram used to write about, the opposition between beatnik and avant-yob. Common is trying to find a position where he’s not mindlessly commercial (Puffy), not creating a falsely criminal self narrative (Biggie), but nor is he disappearing into coffee-shop radical-chic irrelevance. The Stakes are High, and the album is in part a continuation of De La’s debate on that album; the aim is the rendering of reality in all its strange sepias, instead of the bare monochromes of Sin City caricature. The crises pile up: religion on ‘G.O.D.’… city life on ‘My City’ (a Malik Yusuf guest rap*)… And ‘Real Nigga Quotes’ is quickly over and into the agonized walk-through of an abortion on ‘Retrospect for Life’.

‘Retrospect for Life’ sums up what Common wants to do on this record: the re-enchantment of the everyday and its difficulties, or at least the de-mystification of the gangsta pathology. It’s practically Shakespearean in its dramatization of thought: what first promises to be an anti-abortion screed becomes a finely nuanced stream of agonized argument in which Common, almost from line to line, sways between regret and bullish pro-choice radicalism.

I'm sorry for takin your first breath, first step, and first cry

But I wasn't prepared mentally nor financially

Havin a child shouldn't have to bring out the man in me

Plus I wanted you to be raised within a family

I don't wanna, go through the drama of havin a baby's momma

Weekend visits and buyin j's ain't gonna make me a father

The whole thing is soaked in human fallibility; but it's never a question of preaching:

Happy deep down but not joyed enough to have it

But even that's a lie in less than two weeks, we was back at it

The track was produced by James Poyser: Poyser was part of the Soulquarians (as was Erykah Badu who appears on 'All Night Long'), and it was this connection that brought Common to work subsequently with another Soulquarian, Jay Dee (as Dilla was then known), and it's this wider web of collaborations that keeps both Dilla and Common away from the backpacker wastes. The Soulquarians were essentially soul futurists, and even if they didn't make all that many great records in the end, you can't tar them as curatorial classicists.

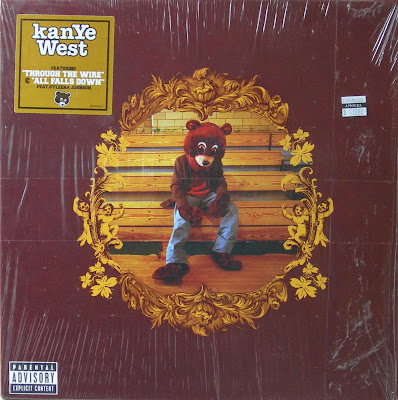

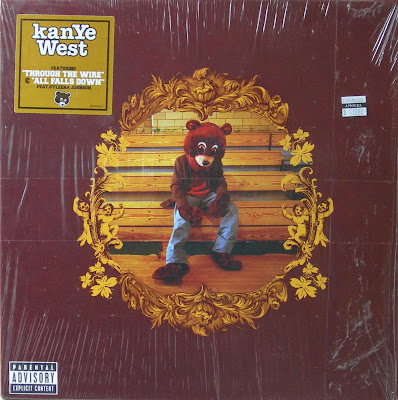

Not sold? Try this then: Kanye West's

College Dropout is patterned on

One Day. Common's album gave Kanye if not the entire architecture of his debut, then definitely the blueprint.

Kanye's mentor as a producer was No ID, who made most of

One Day’s tracks, and Kanye's first studio time was spent working on this album (though he's uncredited and was probably just the one sent out for Chinese). Look at some of the formal features of the two records.

One Day features a track in which Common (with Cee-Lo Green) confronts his anxieties and doubts over religious belief.

College Drop-out has ‘Jesus Walks’, in which Kanye (with Rhymefest) confronts his anxieties and doubts over religious belief.

College Dropout ends with ‘Late Call’, not a track but an outro: a musical bed over which Kanye rambles in conversational prose.

One Day ends the same way, though the genial reminiscences come from Common's father rather than the star himself. Kanye doesn’t have a troubled meditation on abortion and incipient fatherhood, but tracks like 'Through the Wire' and 'All Fall Down' (with its famous line 'Couldn't afford a car so she named her daughter Alexus') do a similar thing in daring to talk about the quotidian, and – crucially – exposing some of the false consciousness in the rap-star model. Both Kanye and Common stage the same ideological battle, wavering between hiphop's tough guy stance and something less theatrical: many-sided, conflicted, something that understands the distance between appearance and reality.

Plus, look at the cover of

One Day again, the colour, the image, and compare it to:

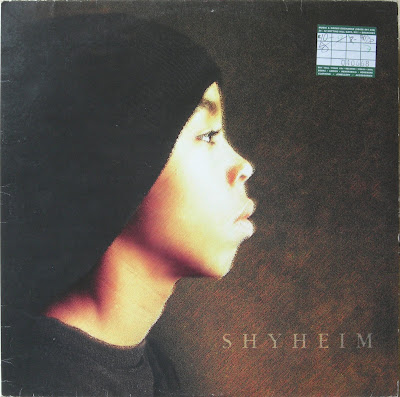

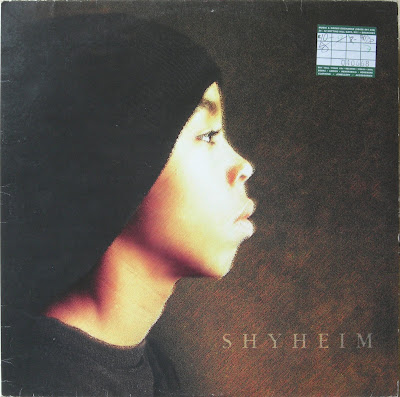

OK, so Kanye a) has a giant bear mascot head on and b) is wearing a blazer, but these are the twists he’s putting on a convention, a basic pattern, represented by Common. Take the head (Kanye’s pop-surrealist chipmunk choruses) and the blazer (his deliberate anti-gangsta provocation as middle-class student) away and you’re left with what? Another commemorative image: one for the family album, like Common with his mother at a Jamaican airport, Nas’s ghostly passport photo, Shyheim’s portait with its stock-school-photo background… These four covers amount to a mini-genre of their own. They're all about that disparity between bravado and honesty, and that's a narrative that's crucial to rap history. History may not record O

ne Day It'll All Make Sense as epochal, even if it was released into an epochal year, but someone took it as a ruff draft, and made good on the promise in that title.

---------------------

* Digression: there's a convention which (I think) is unique to hiphop whereby an artist might have song on his album on which he doesn't feature at all. In other words, a guest rapper delivers an entire track, with the rapper to whom the record is credited not appearing at all. Off the top of my head: 'Wisdom Body' by Ghostface on Raekwon's

Only Built for Cuban Linx... 'The Faster Blade' (all Raekwon) on Ghostface's

Ironman, 'BIBLE' by Killah Priest on GZA's

Liquid Swords...** Some circumstantial connections: Common appears on

The College Dropout, No ID has just produced ‘Death of Autotune’ for Jay Z and Malik Yusuf has just had a Kanye-produced record out on an imprint run by the producer.